Nov 13, 2018

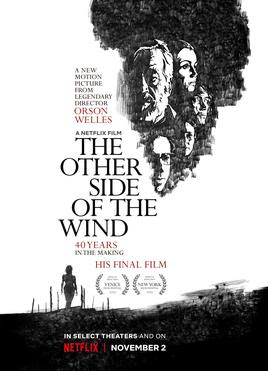

Orson Welles' The Other Side of the Wind Finally Sees the Light of Day

What would Orson Welles have thought of his meticulously crafted final flick The Other Side of the Wind making its debut on Netflix? That’s been on my mind ever since the streaming service announced that the long anticipated film would finally be making its debut on the platform, over forty years after filming wrapped. Would he embrace the wide reach of this technology that arrived long after his death? Or would he scorn a limited theatrical release and focus on home viewing?

As a classic film fan, I’m just grateful to be able to see it. For many years, I wondered if it was even possible. While I kept my expectations low, partly because the director himself was not able to oversee the final edit, I knew that a work by Welles would have something intriguing to offer, whatever the flaws.

The director had reportedly asked filmmaker and friend Peter Bogdanovich (he also appears in the film as essentially himself) to oversee final edits if he was ever not able to do so himself, and as that has happened and Welles’ partner and co-writer Oja Kodar has also had input in the completion of the film, I believe the final product is as close to his vision as could be achieved.

Welles’ story follows Jake Hannaford (John Huston), a director with a Hemingway-style macho vibe on the last day of his life. He has just completed a film, despite the fact that his leading man walked off the set in the middle of a key scene, and he is celebrating his birthday at an isolated ranch with a chaotic band of co-workers, friends, journalists, and hangers-on. That celebration is juxtaposed with scenes from the film, which appears to be a spoof of the intensely symbolic works of European filmmakers (apparently the movie was made very close to the house Michelangelo Antonioni used as a location for Zabriskie Point [1970]).

The assembly of personalities from old and new Hollywood alone is enough to make The Other Side of the Wind a remarkable film. It’s stunning to hear the distinctive voices of the likes of John Huston, Mercedes McCambridge, Lilli Palmer, and Edmond O’Brien saying new things so long after they have left us. Among the party guests is the new wave of filmmaking: Dennis Hopper, Henry Jaglom, Paul Mazursky, and Claude Chabrol among them. They all have plenty to say about film, each other, and Hannaford.

In contrast to the chatter at the party, the stars of the film-within-the-film Bob Random and Kodar remain silent, both on and off the screen. While they don't reveal themselves with speech, both are naked for most of their scenes, a combination of emotional self-protection and physical vulnerability that was new for Welles.

The aggressive sexuality of their scenes together is also a dramatic departure for Welles, who always claimed to be a prude and scornful of film nudity. Kodar was responsible for this change in the director. In addition to being a perfect intellectual match for him, she awakened eroticism in him which he seemed to be learning to process here.

It is in a way fortunate that The Other Side of the Wind is on Netflix, because the film requires multiple viewings to be fully appreciated. On first glance, there’s so much going on. Conversations flying from everywhere, quick edits, different film stocks representing the view of multiple cameras. It can take the whole running time to simply establish who everyone is, and the wide array of their motives and desires. On second viewing, I also got a better feel for the varied rhythm of the film, from the jittery jump cuts of the party scenes to the long, luxurious shots of Hannaford’s last work.

The complex production was filled with enough drama to warrant an entire book: Josh Karp’s The Making of the Other Side of the Wind, my review of which was one of the most read posts ever on A Classic Movie Blog. Film fans have clearly been hungry for this film.

There is also a documentary about the film on Netflix called They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead (2018), and while it is full of fascinating archival footage and frank interviews with key players in the cast and crew, it doesn’t capture the scope and spirit of the project the way Karp has. The film is worth a watch, but the book is essential.

Labels:

Movie Reviews,

Netflix,

Orson Welles,

Streaming

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment