In an especially intense time where world events are concerned, it was a bit much to watch this pair of films full of tension and fear, but I enjoyed them for their good qualities, despite feeling thoroughly drained in the end.

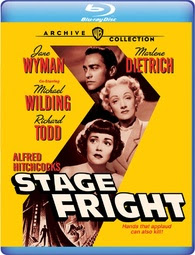

Stage Fright (1950)

I always do a double take when I see Alfred Hitchcock’s customary cameo in Stage Fright. I think “oh yeah, this is a Hitchcock.” It’s an unusual film in the director’s filmography: less perverse, lighter on the thrills, and more focused on quirky characters. It isn’t a top Hitchcock for me, but I enjoyed revisiting the film on a new Blu-ray from Warner Archive.

Stage Fright is set in the theater world. Richard Todd is Jonathan Cooper, an actor having an affair with singing stage star Charlotte Inwood (Marlene Dietrich). In the opening scene, she shows up to his flat in a blood-soaked dress and tells him she has killed her husband. He soon finds himself being hunted for the crime and turns to fellow thespian Eve Gill (Jane Wyman), who has a crush on him, for help.

This is a tricky story, famous for upsetting audiences due to a notorious deception, but it somehow never catches fire. The main appeal is in the cast: Alastair Sim is drily amusing as Eve’s father and actresses including Sybil Thorndike, Kay Walsh, Joyce Grenfell, and Patricia Hitchcock give the proceedings a comic, ghoulish tone. While Todd didn’t affect me one way or the other, Jane Wyman is well-cast as a sharp, but naïve actress, and Marlene Dietrich adds a shot of glamour and sings several songs (she also looks amazing because Hitchcock let her dictate her own lighting, something he seems to have thought she did much better than acting).

It’s an entertaining if minor entry in the Hitchcock oeuvre.

Special features on the disc include a trailer and a short DVD feature-carryover making-of documentary that has major spoilers, so watch after seeing the film.

Edge of Darkness (1943)

I almost couldn’t bear to finish watching Edge of Darkness. In a time where yet another nation came under attack, it was difficult to watch a drama about the wreckage war has brought and continues to bring in our world. It is an excellent movie: beautifully filmed, impeccably cast, and effectively blunt, but it is brutal.

While director Lewis Milestone’s breakout film All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) passionately echoed the pacifist message of its source novel, this World War II era follow-up is about fighting back. That said, both films firmly communicate that no one wins in war. The loss and suffering are too great for victory.

It is the story of a Norwegian village under occupation and how the villagers fight back against the Nazis. The film is relentless in its approach; from the first scene, showing the town strewn with dead bodies to the final, chaotic battle scene. Before that shocking opening moment, there are a few moments of tranquility: a shot of glistening water, snow-covered mountain peaks, and low clouds drifting in the atmosphere. This is how it was before the troubles began.

The cast is uniformly outstanding, with Errol Flynn a revelation in an atypically reserved performance and Walter Huston is solid as the stubborn but wise town doctor. This is a film for women to shine though; there’s a stunning array of complex, strong female characters. Ann Sheridan, Judith Anderson, Nancy Coleman, and Ruth Gordon are all at their best in devastating and fascinating performances.

Despite its horrors, Edge of Darkness is a beautifully made film. Cinematographer Sidney Hickox (To Have and Have Not [1944], The Big Sleep [1946]) does his best work here, finding a balance between the fairy tale quality of the village setting and the horrific nastiness of battle. The Franz Waxman score is also magnificent, capturing the heart and spirit of the determined villagers.

I can recommend this film, but it isn’t an easy watch. As with All Quiet on the Western Front it captures the best of us and the worst of us and that’s a lot to process.

Special features on the disc include the short Gun to Gun, the cartoon To Duck…or Not to Duck, and a trailer.

Many thanks to Warner Archive for providing copies of the films for review.